You Should Read IDLE GROUNDS by Krystelle Bamford

A novel about imagination and loss that insists on taking childhood seriously

It’s been a while since I was a kid, but as I recall, there are two types of childhood games.

The first are games in the playful sense of the word: imaginative storylines enacted for fun, or complex rules created for diversion. One of my favorites, for instance, involved strapping on my rollerblades and pretending to be a figure skater. I’d race my friends to the middle of our cul-de-sac, hoping to earn first dibs. The winner always chose Kristi Yamaguchi; second place, Nancy Kerrigan; and last place, Tonya Harding.1

Despite the applause we heard in our heads, despite the circle stops we insisted were double axels, despite the gravel crunching through our wheels that we swore was fresh ice—we all knew our activity for what it was: a game. I never believed I was a famous figure skater.2

But the second type of childhood game is only a game long after it has ended, when your adult perspective reframes the entire experience. While it is happening, it is intensely, magically—even unsettlingly—real, like the summer I spent hunting for ghosts, convinced that the shimmering air above the asphalt contained spirits trying to communicate with me. My friend and I recorded our observations in a notebook. We named the presences, assuming the shivery air near the garage must be a different entity than the melting air near the roundabout. I also checked out every book I could find about ESP and telepathy in the kids’ section of the library. I doubt my parents have any memory of this, so seriously did I believe in paranormal possibilities, so secretly did I pursue them for a season.

This second type of game—a game that isn’t a game at all—can be found in Krystelle Bamford’s Idle Grounds.

In the 1980s, a group of young cousins spends the afternoon together on and around their aunt’s property. Their families have assembled at Frankie’s house to celebrate someone’s birthday. As the cars arrive, “[c]ousins stuck their legs out from the car doors, always the children first, parents girding their loins behind the steering wheels. . . . Cousins eyed up cousins, standing a full cousin-length away, giving a shy wave while the adults eased themselves out with a dish covered in tinfoil or a six-pack of Beck’s tinkling like a piggy bank” (6).

The number of cousins is indeterminate: “There were ten of us cousins give or take and the tallest and also the oldest one was Travis. He was twelve” (8). Most of the novel is told from a plural-first POV of the cousins, a “we” that conjures the specific collective power of children.3

As the party opens, the cousins crowd into a bathroom at Travis’ behest, where he points out the window. Just when the kids are about give up, they see something inexplicable:

“At first it was just a movement, like when you close your eyes in the sun and things jump about. From the wall of trees hiding the childhood home to Frankie’s shed. A ten-yard dash. . . . Oh, it was fast, you had to give it that. So fast you just knew that whatever it was didn’t want to be seen, but the thing is, we had seen it” (9).

Before they can determine what they’ve seen, young Abi, Travis’ sister, wanders off, and the cousins must not only find her but also deal with the strange thing they witnessed going “[z]ip zip zip” near the edge of Frankie’s property (10):

“‘What should we do?’ one of us asked. And because it was framed as a question which implied the possibility of many kinds of answers, no one said ‘Let’s get a grown-up’ for fear maybe of being too obvious” (54).

Bamford’s narrative voice underscores the loyalty, logical or not, kids hold amongst themselves. It’s a wordless understanding that something big is going on, and the bigness of the thing negates a grown-up’s ability to understand it. The very worst outcome in such a situation would be for an adult to dismiss your concerns as make-believe.

In Idle Grounds, the adults take no heed when the cousins announce Abi’s disappearance. The aunts and uncles insist that Abi was just with them a moment ago, so Travis leads the search for her. As the cousins wander out to their parents’ cars, they notice a change in the atmosphere: “The tree line glistened fatly, more than it had any right, and we knew. It was telling us. It was letting us know” (65).

This scene sucked me into the cousins’ hot June afternoon because I knew, too. A heat mirage may be a ghost or a portal to a parallel universe, but it is nothing an adult can comprehend.

Now and then, the narrator breaks into a singular-first voice. These moments tend to occur when the narrator looks back from an older perspective, or when they do not agree with the collective cousins’ memory. You can see this switch when the cousins find a trail of Oh Henry! bars spilled on the road:

“We sat down, drew up our knees, and ate. Only Owen wasn’t partaking so we peeled a candy bar for him and fed him in elegant bites . . . It was, looking back on it, a lovely meal but not the saccharine orgy we had originally envisioned. It was something to do with the car not appearing when it should have, I believe, and I believe that it was probably our first adult meal, consuming something delicious against a backdrop of foreboding” (90).

Interspersed with the narration of the children’s hunt for their missing cousin are “Intermezzo” chapters that provide information about the adults in the family, including a mediocre novel by their grandmother. Between these interludes and the snippets of conversations the cousins overhear, readers slowly piece together the history of this complex, sometimes troubled family.

A family like any other, that is.

If you haven’t figured it out yet, I’m a sucker for novels about dysfunctional families, but that is not why I loved Idle Grounds. The cousins’ story reminds me of a line from Mary Karr’s memoir The Liars’ Club: “[W]hen you’re a kid and something big is going on, you might as well be furniture for all anybody says to you.”4

Bamford’s achievement, in my estimation, is telling a story of childhood tragedy that always takes the children seriously. You should read it.

A year ago, when I started The Readerly Writer, I had this idea of sharing super-charged book reviews that didn’t “review” a book so much as celebrate it as a font of creative possibilities. The first book I tried this with was The Great Gatsby. (If you’re wondering if you should read the book, you should—here’s why.)

April is always my month of Gatsby. This year, my unit coincided nicely with the novel’s 100th birthday! Whether you teach Fitzgerald in the spring or fall, I’ve got a handful of FREE resources to freshen up your Gatsby lessons.

Background Info Ranking Activity: I open every reading of Gatsby with this quick, low-stakes, and interactive way to introduce historical and contextual facts about the novel. Fourteen facts about Fitzgerald and 1920s America are listed. In Part 1, students read through the information and then rank the facts in order of importance to them as readers. In Part 2, they justify their reasoning. The final page includes my list of sources for further reading.

“Gatsby? What Gatsby?” Characterization Close Reading: After reading through ch. 3, students reread two passages: the end of ch. 1 (Nick sees Gatsby on the lawn) and the middle of ch. 3 (Nick meets Gatsby for the first time). Then students answer guiding questions about diction, tone, and connotations. This is a good activity to practice drawing inferences.

Parallels in The Great Gatsby: This may be my favorite activity with Gatsby. Any time students argue that it’s impossible for an author to think about all the tiny details in their novel, I point out Fitzgerald’s intricate use of echoing scenes. Excerpts from chapters in the first half of the book are paired with excerpts from the second half (through chapter 8). This can be used for individual students, a silent class discussion, or a small group activity (instructions included).

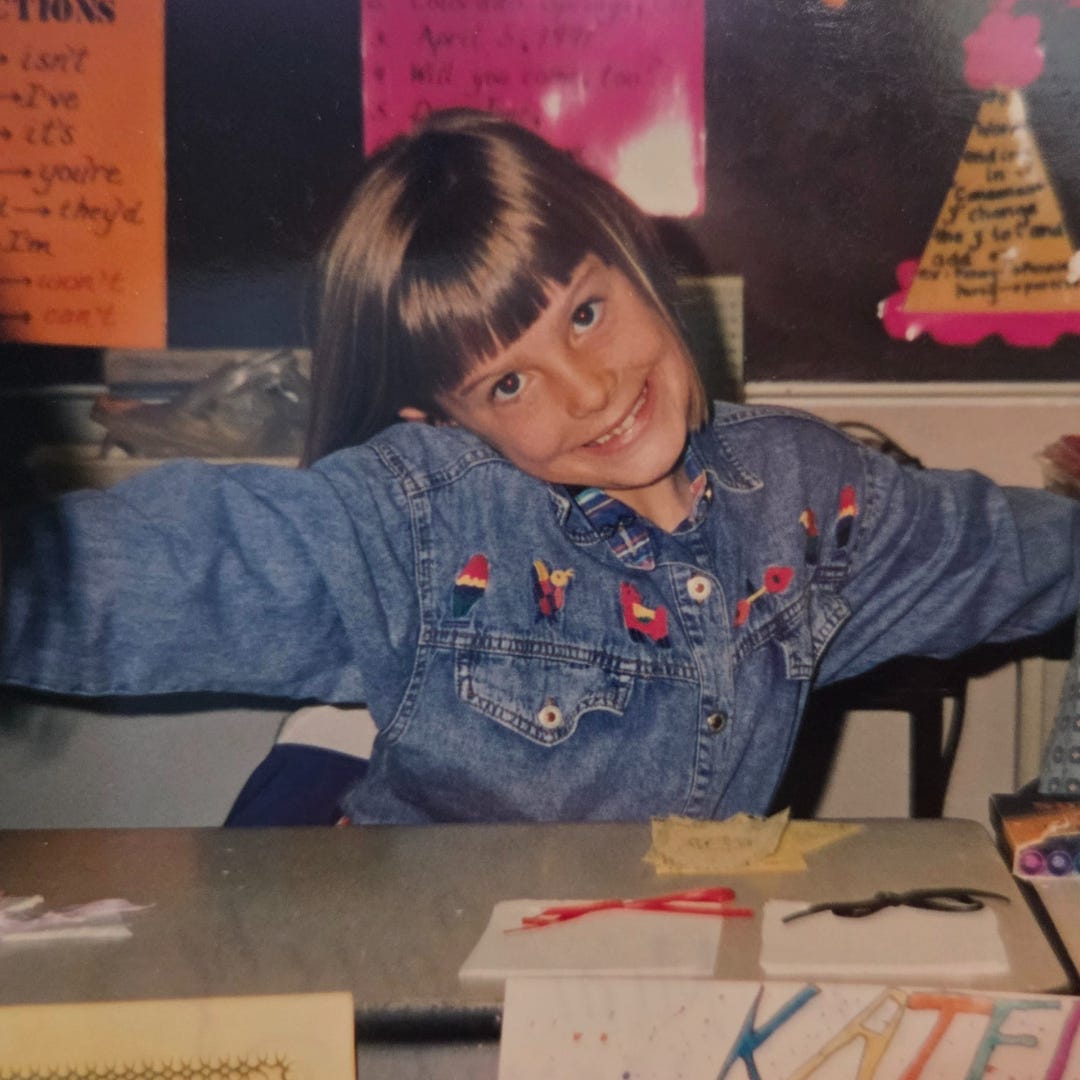

Tell me you’re a child of the ‘90s without telling me you’re a child of the ‘90s.

For the record, I did try to learn how to ice skate, but I gave up after the first six-week session. The instructor told me my butt “wiggled too much” when I attempted to skate backwards.

Another favorite memory: Once, while visiting my uncle in Castle Rock, my sister and I hung out with his neighbors’ kids for an evening. I have no idea how many kids were there, and I don’t remember anyone’s name, but nothing can match the intensity of the lava game we played on the swing set that night.

I use the opening pages of The Liars’ Club as a mentor text for a narrative essay every year. I also wrote about it for my master’s thesis: “Reconstructing Blank Spots and Smudges: How Postmodern Moves Imitate Memory in Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club”