You Should Read THE APARTMENT by Ana Menéndez

Ana Menéndez writes about the bonds, both physical and spiritual, that connect tenants of a single apartment over seventy years.

Check out a book recommendation from author Laura Pritchett after my review! Click on “Read in app” to read the full post.

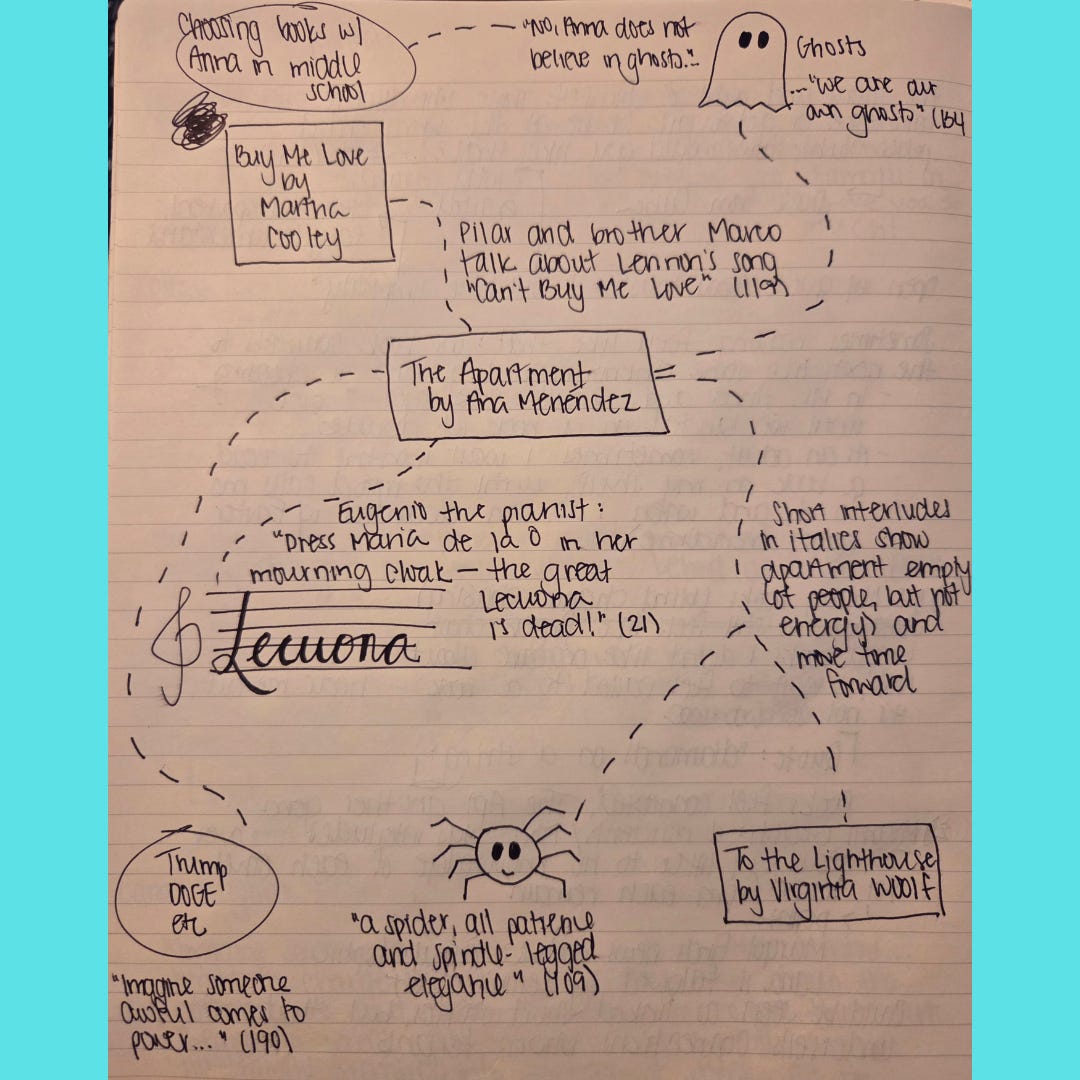

In sixth grade, I chose books like this: I’d go to the school library with my best friend, close my eyes, and run my finger along the spines. If I landed on a book with two copies, we’d each check one out. If I didn’t, we’d take turns repeating the process until we did.1

Nowadays, I still choose my books by feeling, but instead of waiting for my finger to brush against a duplicate title, I wait for a book to call me. The sensation is like an internal tug, drawing me toward a title I may have ignored on my nightstand or walked past at the library for months.

It sounds ridiculous, I know!2 But take The Apartment by Ana Menéndez: I wandered the library at the beginning of February on a cold and gloomy weekend, the weather gray and uninspiring, all of us waiting impatiently for the bluebird days of a Colorado spring. The sun-washed color palette on the book’s spine cheered me, and when the flap mentioned “a Cuban concert pianist,” I stopped reading and put it in my bag immediately. I recently discovered the music of Cuban composer Ernesto Lecuona and am learning two of his piano pieces. I needed to know more about this Cuban pianist; I needed to read this book.

This brief connection was a fitting introduction to The Apartment, which is itself about the bonds, both physical and spiritual, that connect tenants of a single apartment over seventy years. Menéndez tells us the apartment is “a castle of sublime limpidity, and the rooms connect to one another like diamonds on a string, infinite” (80).

Throughout the book, apartment 2B at the Helena in Miami Beach turns over eleven times, its occupants ranging from newlyweds in 1942 to a troubled painter in 2012. The tenants have little to no knowledge of each other, yet traces remain from each. An Argentine refugee in 1984 finds a newspaper article about the death of an earlier tenant, and paint splattered by one lodger raises questions for the next.3 The premise could lend itself to a set of linked short stories, and there may be readers who view the book this way. But that interpretation undersells Menéndez’s vision.

Two structural choices anchor this book as a novel. First, italicized interludes join one tenant’s story to the next. These interludes, reminiscent of the middle “Time Passes” section in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, personify the apartment. “Homes also dream; they shelter themselves,” Menéndez writes (80). With an omniscient perspective, these passages also offer a break from the close third point-of-view of characters who live in the apartment. We overhear conversations from maintenance workers and observe mice and insects that reside in the empty space. One of my favorite images spans the gap between a Colombian immigrant carrying out a green card marriage and a journalist fired after the financial crisis:

“From the corner formed where the refrigerator meets the counter, there drops another, more delicate shadow. It sways beneath the night light, centimeters from the countertop: a spider, all patience and spindle-legged elegance. She hovers for a moment before hauling herself back up” (109).

As my second-grader tearfully informed me after reading Charlotte’s Web with her class last week, spiders don’t live very long, but Menéndez’s depiction of the spider makes me imagine this very same insect hovering above Sophie in 1942 and Eugenio in 1963 and Marilyn in 1994 and Lana in 2012. When Lana eventually moves into 2B, she traps the apartment’s mice. Rather than killing or releasing them, she keeps them safe in a cage with “[t]hree levels and five exercise areas” (197). The mice, like the people who live in 2B, are refugees.

One of Lana’s neighbors, Fefa, escaped to Miami Beach from Cuba. Lana tries to avoid Fefa and her crazy outbursts, but she can’t avoid her forever. Fefa pounds on Lana’s door one night and describes her experience in Cuba:

“Imagine someone awful comes to power in this country, begins to change everything, begins to divide the country, to shut down the press, to co-opt the courts. Begins to wreck your institutions one by one. Installs his family members into positions of power. All for the glory and profit of himself. Those who disagree can leave. Or go to jail. Or be at the wrong end of police clubs. How would you like that?” (190)

Fefa, I would not like that. Actually, wrong verb tense, wrong pronoun: I do not like this at all!4

Neither does Lana, and while she doesn’t know how to respond to Fefa or her other busybody neighbors, she can’t help but listen to them.

Lana’s story is Menéndez’s other novelistic choice. While the first two-thirds of the book cover ten occupants, the final third is devoted to Lana . . . and the ghost/spirit/energy of a previous tenant.5 Lana, like other residents before her, is a painter. She’s troubled by the death of a loved one and tries to isolate herself with her art, but her neighbors in the building refuse to let her wallow. They bake for her. They tell her stories. They deny her desire to disconnect from society—and that, to me, is what The Apartment is about.

There’s no way around it: We are all products of and subject to our particular historical moment. That doesn’t mean, however, that we are limited to it. In The Apartment, the tenant who posthumously resides with Lana, knows this all too well: “If only I inherited a different story . . . But I was caught in my small human vanities. The world moves forward. The past is immutable concrete, subject only to erosion. But we can alter the future, even after death, we can map a new story” (222-3).

Our stories might seem small, might seem like a collection of “small human vanities.” But when we share them, as Lana learns from her neighbors, they become larger than us—they outlast us—they, if we are paying attention, map out a way to live better.

Reading as a form of paying attention means that we must ask ourselves, in each story, whose perspective isn’t heard and what they might say if given a chance.6 Reading The Apartment offers snapshots into lives of Americans and immigrants who are often ignored. I’m not going to stand on a soapbox and proclaim that reading will save us from hatred and discrimination. It won’t!

But do you know what might?

Listening, like Lana does, to stories from people we don’t at first like. From people that society labels “crazy” or “wrong.” From people who keep secrets in order to stay alive.

If you’re not quite ready to listen yet, that’s okay. Read The Apartment until you are.

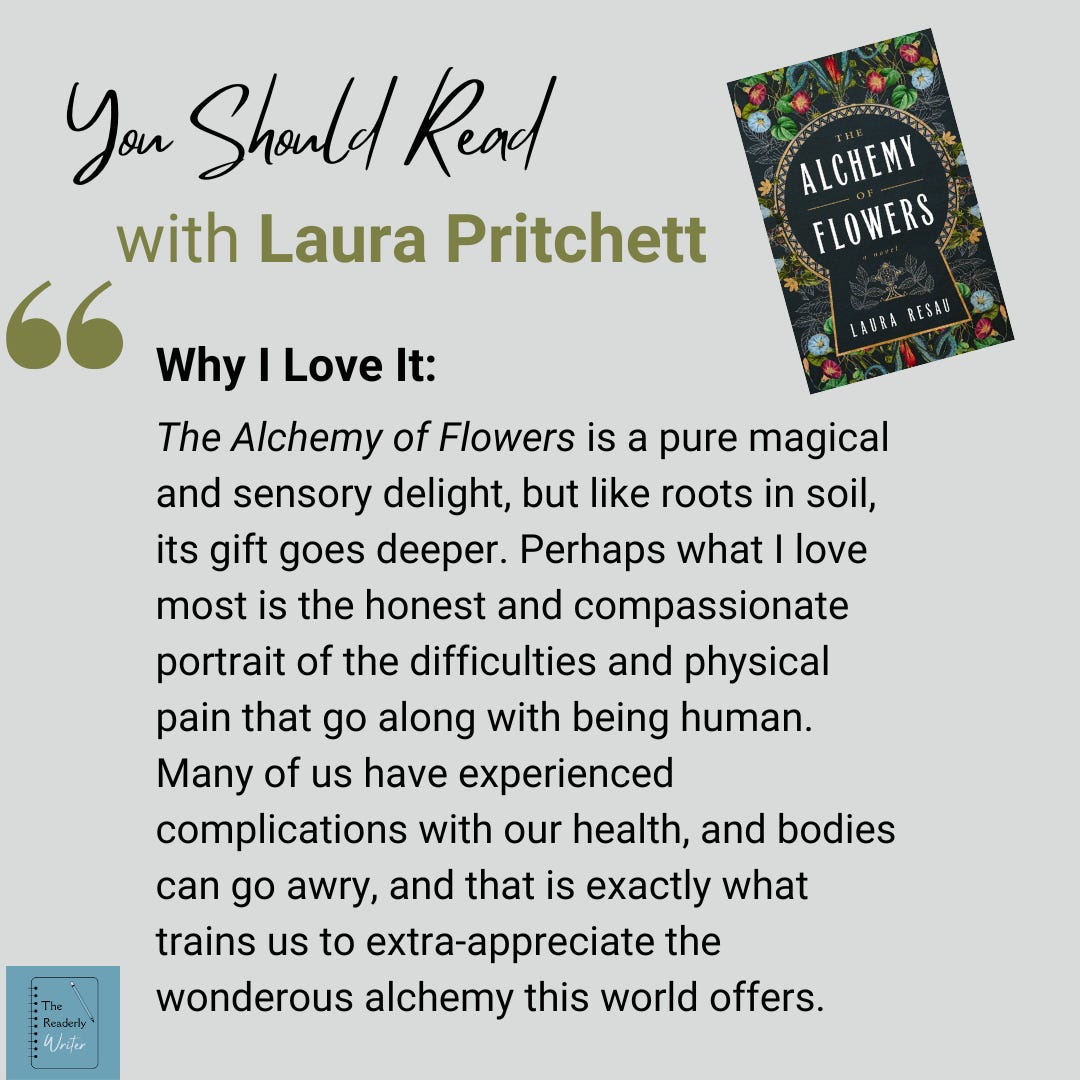

As I told Laura Pritchett in a recent email, I’ve been a fan of hers since I read “Under the Apple Tree” in The Sun when I was in college. My biggest pitch to her, though, was that in the ongoing book club my stepdad and I have had for over 15 years, we’ve read both Hell's Bottom, Colorado and Stars Go Blue by Pritchett. He liked them, too! That’s a big deal, considering his go-to genres are political biographies and Russian doorstops.

Laura Pritchett is a Colorado-based author who directs the MFA in Nature Writing at Western Colorado University. She’s the author of seven novels, two nonfiction books, and editor of three anthologies, and her work has been the recipient of the PEN USA Award, the Milkweed National Fiction Prize, the WILLA, the High Plains Book Award, and several Colorado Book Awards. I’m currently halfway through her latest, Three Keys, and it was tough to put it aside to write for you today! Laura thinks you should read The Alchemy of Flowers by Laura Resau (forthcoming July 2025).

Thanks, Laura!

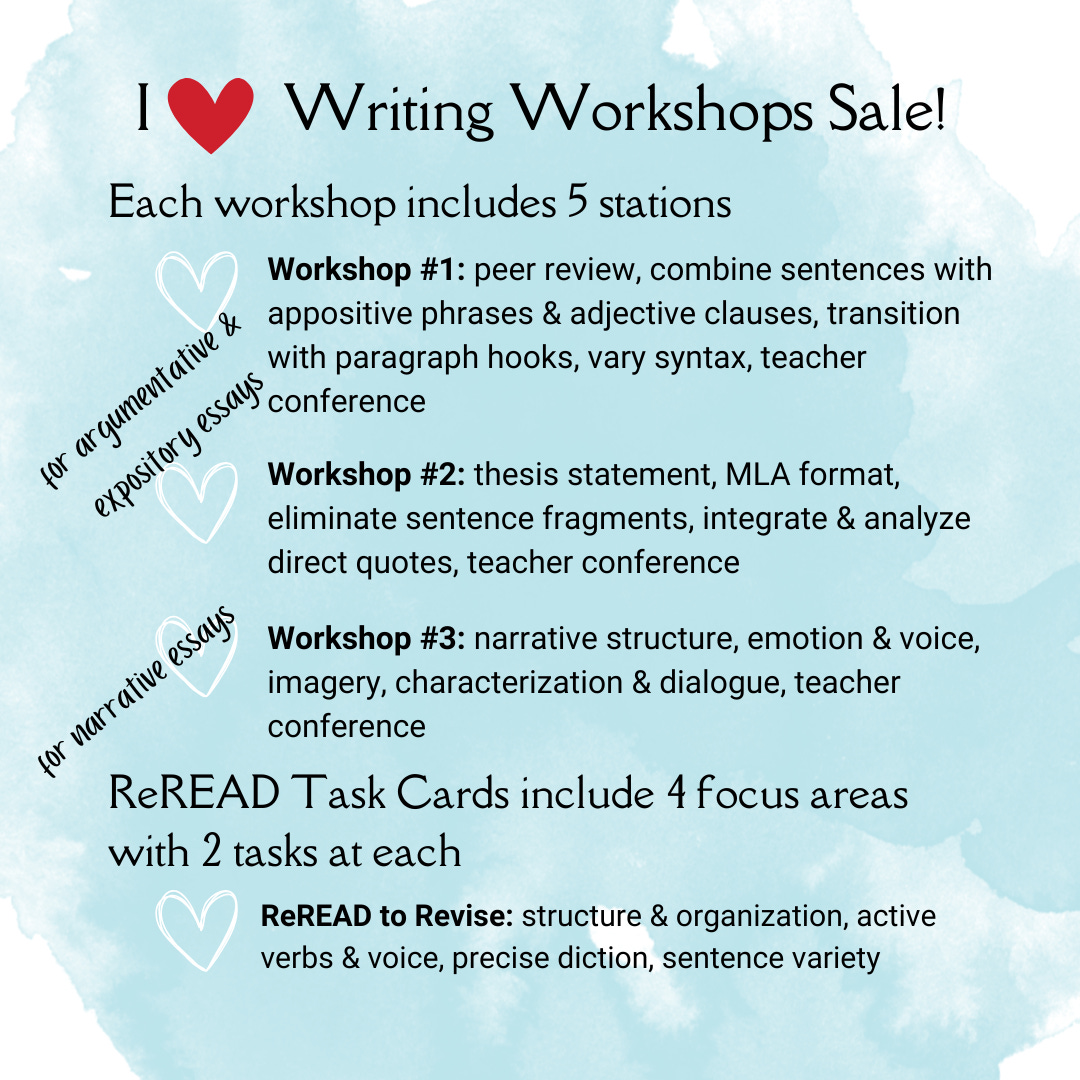

In honor of how much I love writing workshops in the secondary classroom (and not, say, because of a stupid, arbitrary holiday in which my husband refuses to partake), I’m discounting my writing workshop activities on TPT! I’ve extended the sale through February 21. In addition to the 4 discounted workshops (usually $3/each, now 20% off), there are also some free workshop activities. These are resources I’ve built over 12 years of teaching—and resources I wish I’d had as an early teacher.

I’d love to hear from any educators who use resources from The Readerly Writer about what works for you and what you wish you had.

Thanks for reading!

Kate

Full disclosure: I read some really dumb books this way. I don’t recommend this method.

This is not any more ridiculous than the time I showed up at my dad’s house for the weekend to find my then-stepmom had rearranged my room without my permission, as if feng shui can make tweens any less tweeny.

Painting is an important motif in this book. Two painters inhabit the space, and maintenance workers refresh the paint between occupants. I could have written an entire essay about painting and art in this book!

When I read this passage, I shivered. Menéndez published this book in 2023, like a ghost from the future. Then again, she was here for Trump round one like the rest of us. It wasn’t all that hard to prognosticate what round two would look like.

One character who doesn’t believe in ghosts believes that “we are our own ghosts, dragging our mournful pasts behind us forever” (134).

These questions guide my teaching philosophy: (1) What does the story reveal about the human experience? (2) What does the story suggest or challenge about our beliefs? (3) Whose story isn’t heard? What might they say if given a chance?

I'm going to put this one on my list!