You Should Read THIS STRANGE EVENTFUL HISTORY by Claire Messud

Her books are pinpointed in time for me, the way people remember where they were for the moon landing (not alive) or 9/11 (a high school sophomore).

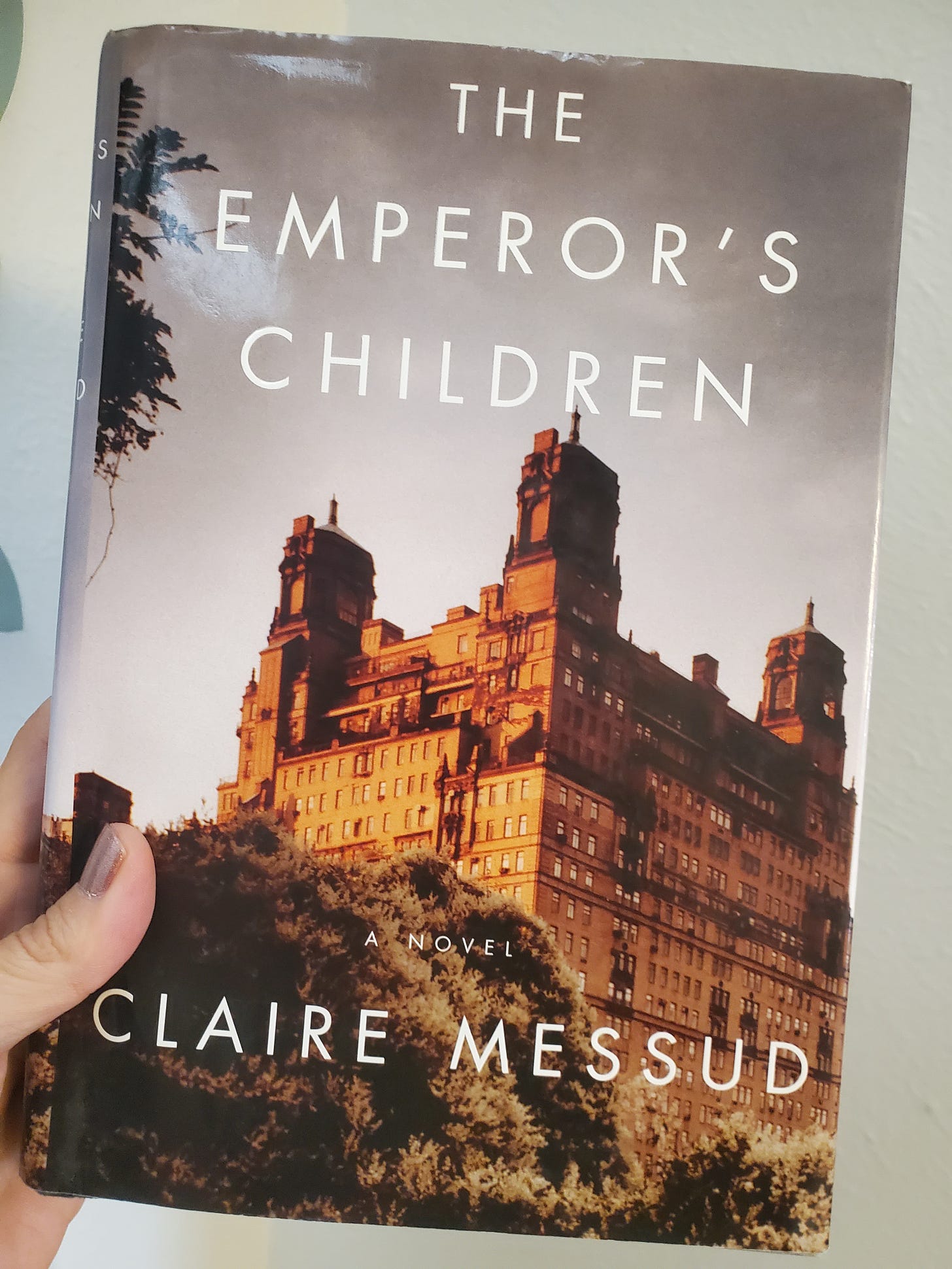

I first came across Claire Messud through her 2006 novel, The Emperor’s Children. I bought the book in hardcover, which was a vote of confidence on my limited college-student budget. There I was, interning at a local newspaper and dreaming of working in publishing. The story of three friends approaching thirty in New York City, that wonderland of the bookish imagination, spoke to both my aspirations and my fears. When I listed it as a favorite book to a coworker, she told me she couldn’t get past Messud’s descriptions. I think she may have used the word “tedious,” at which point my estimation of her, at least on a literary level, plummeted.

Tedious? Never. Messud’s writing is transporting. She could spend thirty pages describing asphalt being patched on a 90-degree day, and I’d still be enchanted. I’d also recognize an obscure emotion in that asphalt patcher that I’ve felt but never admitted to myself. The details Messud writes into her scenes turn the words into landscapes. Reading her novels feels like meandering through an art collection. The images are evocative, the sentences are surprising, the characters are memorable, and the sense of place lingers with me after I’ve closed the cover.

As a case in point, take this sentence from her most recent novel, This Strange Eventful History:

“By breakfast time, the sun had burned the sky clear, its impeccable blue lighter, brighter than the reflecting waves beneath, fringed by occasional whitecaps, dotted by vessels and buoys, a surfacing submarine in the distance, its little men lined upon the deck, all the visible universe a kaleidoscope of blues from Prussian to celeste.”

I am in Toulon, France, when I read that sentence. But that’s not the only place I get to visit. This Strange Eventful History jets from Greece to Algeria, from Canada to Australia, from the United States to France, following three generations of the Cassar family.

Gaston, the patriarch, grows up in Algiers and hopes to raise his family there. But when German forces occupy France, the French colony falls into limbo, and so do the Cassars and thousands of other pied-noirs. François, Gaston and Lucienne’s son, studies in America and chases a sense of home from one country to the next. Toward the end of his life, François reflects:

“What had the expression been, back in the day—his own family was already long gone, but the pied-noirs used to say ‘the suitcase or the coffin’—that was it. And he’d chosen, time and again, the suitcase. Pack up and move on.”

His wife, Barbara, doesn’t appreciate his suitcase-first approach to life. She’s a Canadian homebody who understands neither his restlessness nor his drinking. François, for his part, cannot abide his wife’s cool, reserved demeanor. He longs for the intimate devotion he witnesses between his parents.

Despite often coming at one another from cross purposes, François and Barbara still share the connection of a lifetime lived together. I recently wrote about 2 A.M. at the Cat’s Pajamas, which is a completely different type of book, but there is a line from it that applies to François and Barbara. In Marie-Helene Bertino’s novel, characters understand each other “innately . . . the way you know on a flight, even with your eyes closed, that a plane is banking.” François and Barbara may never understand each other on a logical level, but they know each other on an intuitive one, and that alone is worth something.

Seeing her aging husband from afar, Barbara “[feels] a surge of emotion. Was it purely joy or also relief? That they were rich, still, in minutes, inshallah in years, that the now-chill air could still kiss them, that they could fight, dither, joke, read, laugh, complain, be” (346). Like a plane banking as it descends toward land, Barbara and François come home to each other time and again, despite the emotional turbulence they encounter (and create) in each other.

Their daughter, Chloe, forges her life as an American but looks to her family’s past in her grandfather Gaston’s journal, a collection of binders filled with 1,500 pages of handwritten recollections (Messud’s grandfather’s handwritten memoir inspired much of this book). The novel includes multiple points-of-view, but Chloe’s is the only one in the first-person. In the prologue, she introduces herself to us as the (as yet unnamed) narrator:

“I’m a writer; I tell stories. I want to tell the stories of their lives. It doesn’t matter where I start. We’re always in the middle; wherever we stand, we see only partially. I also know that everything is connected, the constellations of our lives moving together in harmony and disharmony. The past swirls along with and inside the present, and all time exists at once, around us.”

I once listened to Min Jin Lee (you should read her, too!) speak about how she likes to begin her novels with a thematic statement that guides her story. If Messud were to do the same, the sentence could be this: Wherever we stand, we see only partially. This Strange Eventful History explores what we can and cannot know about our family members and the ways in which families both shape and challenge our expectations of ourselves, of our futures, of how we want to love and be loved, to know and be known, to remember and be remembered. Messud’s novel argues for the beauty in seeing “only partially,” a view that our human desire for control often resists.

Which brings me back to my young, book-eyed self in 2006, planning a career as an editor or publicist or something, anything, that would grant me access to the literary world. What a partial view I had! My short-lived “dream” job started and ended at an academic imprint, and I’m happier now in the English classroom than I ever was in my publishing cubicle. I never would have guessed that seventeen years later, I’d get the opportunity to workshop a novel of my own with the lovely, talented Claire Messud at Lighthouse Writers in Denver. From where I’m writing now, I have two completed manuscripts, a third half-finished first draft, a handful of short pieces published in hidden online corners, and no agent (yet).

But that's just a partial view. Who knows what I’ll see of my writing life when I look back seventeen years from now?

I’ll guarantee you this, though: I will remember reading This Strange Eventful History. For me, Claire Messud’s books are pinpointed in time, the way people remember where they were for the moon landing (not alive) or 9/11 (a high school sophomore).

When the World was Steady? I was a recent college graduate at the DU Publishing Institute, realizing I couldn’t afford to / didn’t want to / wasn’t brave enough to move to NYC.

The Woman Upstairs? I read it in a single day on a Nook (remember those?) in the first house my husband and I bought together.

The Burning Girl? That was another hardcover purchase, read in our second house during the rare days when our one-year-old’s nap coincided with our three-year-old’s quiet time.

This Strange Eventful History? I read this book over the span of four days during a summer spent ferrying my daughters, now seven and nine, to various camps and activities. During my daughter’s gymnastics class, chalky dust hung in the balcony air, the spring-loaded floor thumped as older girls tumbled across it, and I, transported, read This Strange Eventful History.

You should read it, too.