You Should Read DAMNATION SPRING by Ash Davidson

A tale of high climbers, spar trees, and the expertise of the undervalued and overlooked working class

Check out a You Should Read author interview with Christine Grillo after my review! Click on “Read in app” to read the full post.

As one character in Damnation Spring tells another, “You get a miracle in life, you take it” (315).

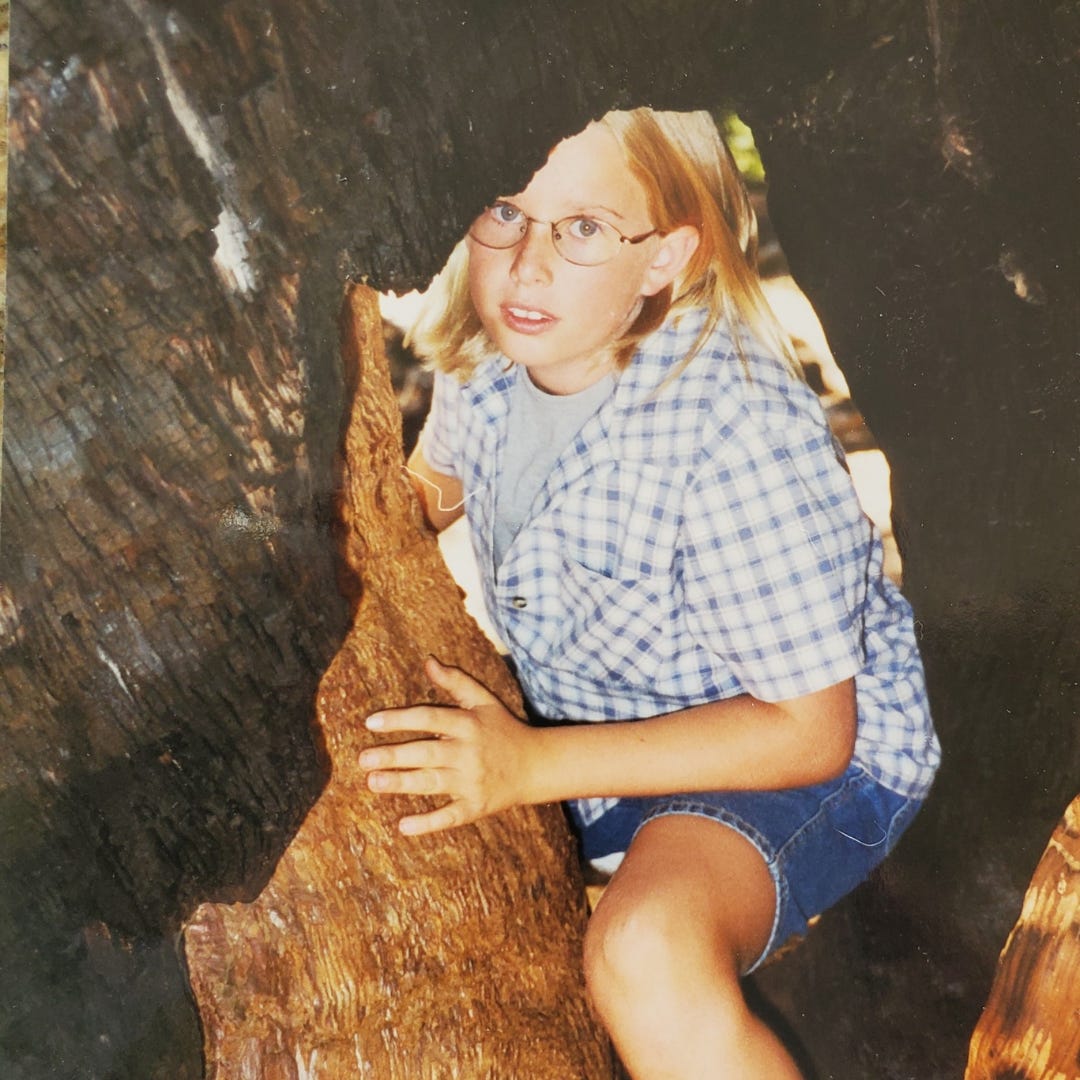

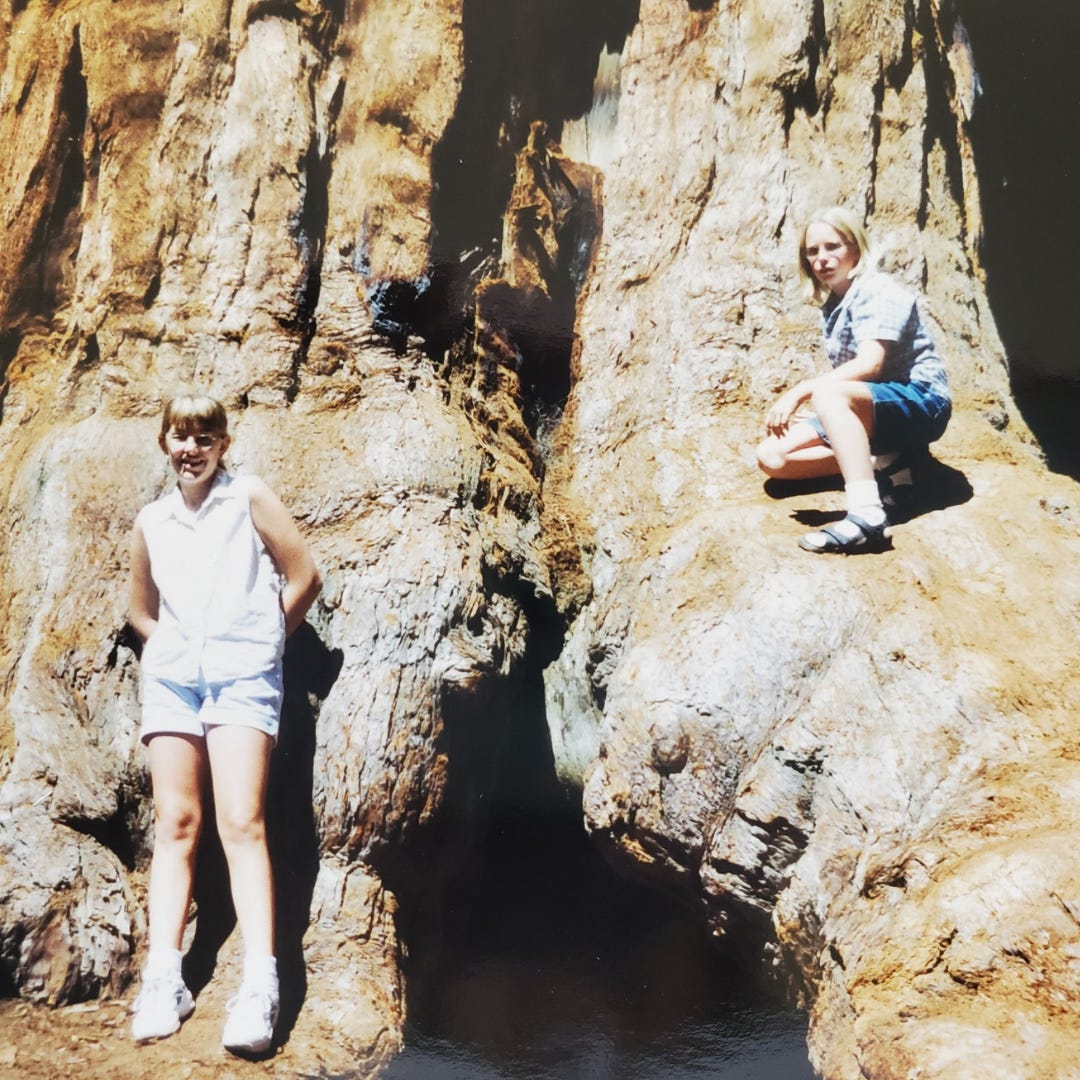

To paraphrase: Your sister gives you a good book, you share it—which is another way of saying that you should read Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson.

It’s 1977 in northwest California. Rich Gunderson has spent his life among the redwoods, and since the age of fifteen, he’s worked for Sanderson Timber Company. He’s proud of his trade, a pride Davidson gives voice to with her detailed and knowledgeable descriptions of logging. Although I could imagine a place, say somewhere that rhymes with RoodGeads, where complaints might be lodged against Davidson’s use of technical jargon, the passages about high leads, spar trees, chokers, guylines, and pumpkins demonstrate the expertise of an overlooked and undervalued working class. The terms are a sign of respect, not any sort of authorial flex.1

At fifty-three, Rich is already past the average lifespan of a logger. His incessant aches and stiff knees remind him daily that he can’t be a high climber forever. When presented with the opportunity to purchase a parcel of land, Rich goes for it. It’s not the land he’s interested in: it’s the 24-7 tree, “a monster, grown even wider now than the twenty-four feet, seven inches that originally earned her the name, three hundred seventy feet high, the tallest of the scruff of old-growth redwoods left along the top of the 24-7 ridge” (7). As the new landowner, he stands to make “twenty years’ salary for a few months’ work” if he can cut down the 24-7 and get it to a lumber mill (22).

One problem: Rich can’t access the tree until Sanderson clears Damnation Grove and runs roads near the 24-7 ridge—and environmentalists are working to undermine the logging company’s efforts.

Oh, and one more problem: Rich neglects to tell his wife, Colleen, that he’s gambled all of their savings and taken out a huge loan for the 24-7.

Colleen has problems of her own. She desperately wants to have another baby, a sibling for their five-year-old son, but she keeps having miscarriages. As a midwife, she also notices a concerning trend of birth defects in women around town. When her ex-boyfriend, Daniel, returns to town as an environmental scientist, he warns her the water her family draws from Damnation Creek may be contaminated by the herbicides sprayed by both the logging company and the forest service.

Daniel is an enrolled member of the Yurok tribe. He’s returned to the area with funding to study the water quality. He tells Colleen, “Even with the hatcheries, the coho run’s down to almost nothing. . . . It’s our whole life, our whole identity, as far back as anyone can remember, you know? . . . We can’t be Yuroks, without salmon” (39).

Most people around town discredit Daniel as just another hippie, stirring up trouble in one place before moving on to the next trendy protest. As Colleen’s sister bitterly remarks, “Can’t mow your lawn without somebody showing up to protest. . . . What do they wipe their butts with? That’s what I’d like to know” (32).

But the tragedies continue to pile upon the small community. After a swath of trees are cut down, there is nothing to hold the land in place, and a mudslide all but buries a neighbor’s house. When Colleen checks on her, she finds “[a] narrow, waist-deep trench tunneled around the cabin’s side” (322). The negative environmental effects of logging and spraying become impossible to ignore.

Despite the life-or-death stakes and the high emotions running through the community, Davidson’s prose remains unsentimental. She tells the story with a firmly realistic narrative, building characters as flawed as the burled trees2 around them. And this, perhaps, is the biggest problem of all: The community witnessed precursors to this devastation and didn’t take action. Lark, Rich’s friend, lost his wife and two sons in a flood years ago. When Colleen drives through the area, she crosses “Gold Bear Bridge” and passes “the two tarnished bears where the old bridge had stood, before the flood. A logjam had bashed against the footings, pounding until they gave way. She’d forgotten these bears, still guarding their invisible bridge” (116).

The bears’ invisible bridge is the warning sign the logging industry chose to ignore. Davidson’s book is a reminder for us to keep an eye out for the forgotten bears of our own age.

Sometimes people ask me if teaching high school reminds me of being in high school, and it generally doesn’t. But do you know what does? Asking authors whose books I really, really love to share a book recommendation with me. Luckily, Christine Grillo didn’t turn me down like a sweaty freshman who asked her crush to the dance.

Christine Grillo is the author of Hestia Strikes a Match, which I gushed about here. You can find her on Instagram at christine.grillo. She supports BookShop.org and thinks you should read All Fours by Miranda July.

Thanks, Christine!

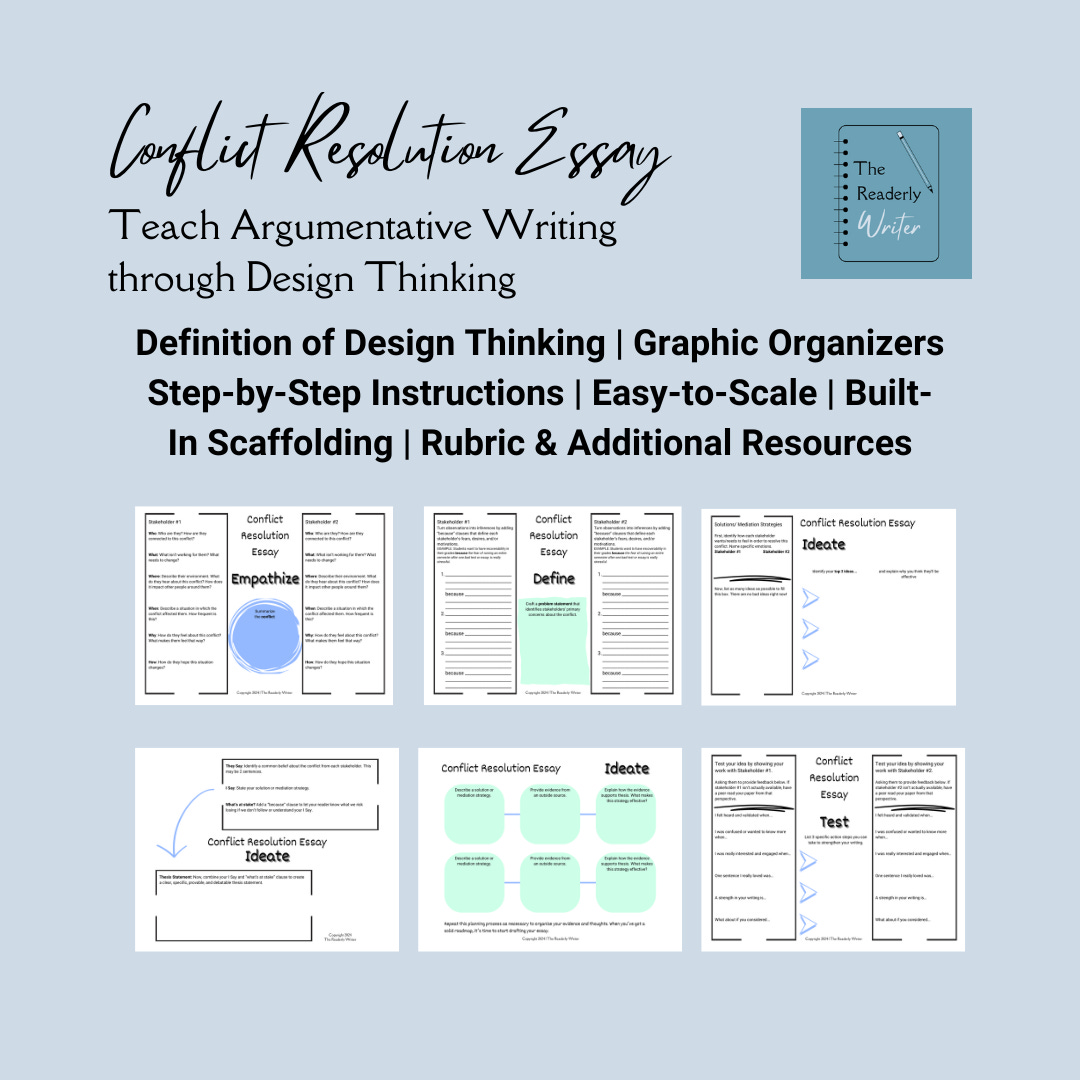

As the tension in Damnation Spring rises, the community gathers for a meeting where stakeholders from both sides share their views. The scene reminded me of an argumentative writing unit I teach using design thinking. Identifying and evaluating the perspectives of stakeholders is an important step in the design thinking process, which takes students through five phases: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. Although it’s more commonly used in the business world, I’ve found it a useful tool in the writing classroom. You can find my 11-page essay planner on TPT to walk students through a conflict resolution essay.

Take this passage where Rich is speaking to a new kid on the logging team: “This is a high-lead show. That means we use a spar tree, that big one, where we dumped the gear, as our center pole, like the mast on a ship. Spar’s got to withstand a lot of weight. Our faller will drop a ring of trees around our spar. Once that’s done, I climb up, trim off her branches, and cut her top off. Then we haul the blocks—big pulleys—up the spar and rig the cable system that maneuvers the logs” (53).

Yes, there is quite a bit of logging jargon in Rich’s chapters, but the effect reminds me of a fantasy novel. To be honest, I don’t really read fantasy. (Give me painfully realistic dysfunctional families over dragons any day.) The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin is the last fantasy book I’ve read in…ever, perhaps? (Yet another solid recommendation from Tiffany Quay Tyson! See what she thinks you should read here.) But Jemisin models the thorough world-building fantasy requires. When done well, fantasy immerses readers in a particular place with rules and conventions that, however crazy they may seem, make total sense in that world. Davidson’s writing about the work of loggers functions the same way. While reading, I accepted the fact that I don’t know all of the logging jargon and can’t totally picture the process Rich is part of, but I approached it as I would a wave that washes over you and then retreats, leaving a layer of saltwater to dry on your skin.

A burl is a deformation that grows on a tree.

I think I'm one millionth in the library line for ALL FOURS. I'll have to read DAMNATION SPRING in the meantime thought. I read HESTIA on your recommendation and totally loved the book :)

I love these recommendations, Kate!