You Should Read PENITENCE by Kristin Koval

This debut novel suggests that a reason why is less important than the redemption sought after a cruel or careless act.

Sometimes I read to escape stressors in my life; at other times I read to explore new places or historical periods.

But when the year is waning and days are shortening; when I am sacrificing weekends to the looming semester deadline; when I am questioning all the inescapable holiday traditions that drive me to equal parts madness and nostalgia; when I am reflecting on all I have yet to accomplish—then, I read to feel less alone.

I read to find that tiny spark of sameness in a totally made-up character.

’s Penitence, which probes the limits of forgiveness, offers just that spark. It opens in a fictional Colorado ski town called Lodgepole, where thirteen-year-old Nora has committed a seemingly unforgivable act: the murder of her fourteen-year-old brother, Nico. Their parents, Angie and David, respond so differently that their marriage is threatened as well. Nico suffered from juvenile Huntington’s disease, a terminal diagnosis. Was this a mercy killing? Did Nora hope to prevent her brother’s inevitable descent into Alzheimer’s1, a disease that is also killing Angie’s mother? Was it an accident while Nora was handling David’s work-issued firearm? Or worse: was Nico’s death a typical sibling spat-turned-tragic mistake when Nora gave into a split-second impulse?

For Nora’s defense, David solicits help from Martine, a local lawyer. When Martine visits Nora at the juvenile detention center, she’s met with silence “because [Nora] can’t—or won’t—remember the what or the how or even the when” (61). Martine recruits help from her son, an NYC-based lawyer, but Julian cannot get anything out of Nora either. And to complicate matters further, Julian is not only Angie’s ex-boyfriend, but also an eyewitness to an accident that killed Angie’s younger sister years ago.

Despite the prevalence of lawyers and deaths, this is no Law & Order-style whodunnit. I have no doubt that Koval, a former lawyer herself2, could write a fantastic courtroom drama, but I appreciate that this novel concerns itself more with learning how to live in the aftermath of trauma, both self-inflicted and accidental, rather than with uncovering the reason behind it. Nora’s story suggests that a reason why is less important than the redemption sought after a cruel or careless act.

And that quest for redemption? Well, that’s the tiny spark I sought when I opened the book.

At one point, reflecting on Angie’s sister’s accident, Julian recognizes that he and Angie have completely separate memories and interpretations of their shared experience. He thinks, “Our fault meant something different to Angie than it did to him. After all these years, he still didn’t know what was his fault and what was hers. . . . Maybe he still didn’t know what our fault meant to him” (101). Julian’s uncertainty points out a linguistic shortcoming. When we think of fault, we think of blame, and when we think of blame, we long to point to a specific person or event that caused hurt. But there are degrees of both blame and fault, nuances that exist in reality but are not captured by either word. I nodded along with Julian when he reached this realization because I knew exactly what he meant—or perhaps, this fictional character knew how I felt.

Here’s another glimmer: As Angie tries to carry on after Nico’s death, she returns to painting, a passion she left behind along with Julian years earlier. Painting provides her with structure and purpose. It grounds her in something she can control when everything else is whirling away from her. When she brings watercolors to the detention center, painting also connects her with Nora once more. Angie reflects, “Even if her life is falling apart, she is still this: an artist. She creates beauty; she finds beauty. She is not defined only by her failures” (242). Swap out artist for writer, and I think: Same.

Tiny sparks of sameness abound. If you’re looking for a wise novel to help you interrogate what it is to be human, give Penitence a try when it comes out on January 28, 2025. (And then check out what Koval herself thinks you should read!)

Whether you’re heading back to students you know or meeting an entirely new group of kids, it’s important to set a positive tone for the spring semester. We need at least one solid month before sinking into the pit of despair that is February (and don’t get me started on April…).

Here are a few no-prep ideas. (You could even skip them right now and just bookmark this post for your first day back after break. I plan to do absolutely NO PLANNING over break myself!)

The Writer’s Costume: I have a new set of students starting a semester-long composition class in January. On our first day together, I share two paragraphs from Margaret Atwood’s Negotiating with the Dead about what she calls “the writer’s costume.” Reflecting on the tension between the expectations and realities of writing, she says, “No writer emerges from childhood into a pristine environment, free from other people’s biases about writers. All of us bump against a number of preconceptions about what we are or ought to be like, what constitutes good writing, and what social functions writing fulfills, or ought to fulfill.” I’ve included the full two-paragraph excerpt as well as a reflective prompt on a FREE one-page handout here. You can easily use this resource even if you don’t teach writing! Just alter the noun in the reflection so students are thinking about what costumes, or personas, they wear as, say, artists or scientists or musicians or leaders.

Last-Now-Next Reflection: This resource (pictured below) is FREE on TPT. I modeled it on an Instagram trend where you post a stack of what book you read last, what book you’re reading now, and what book you will read next. The same format is a useful way to reflect on your growth and look toward your future. This quick & super adaptable template guides your students to reflect on three specific skills of their choosing.

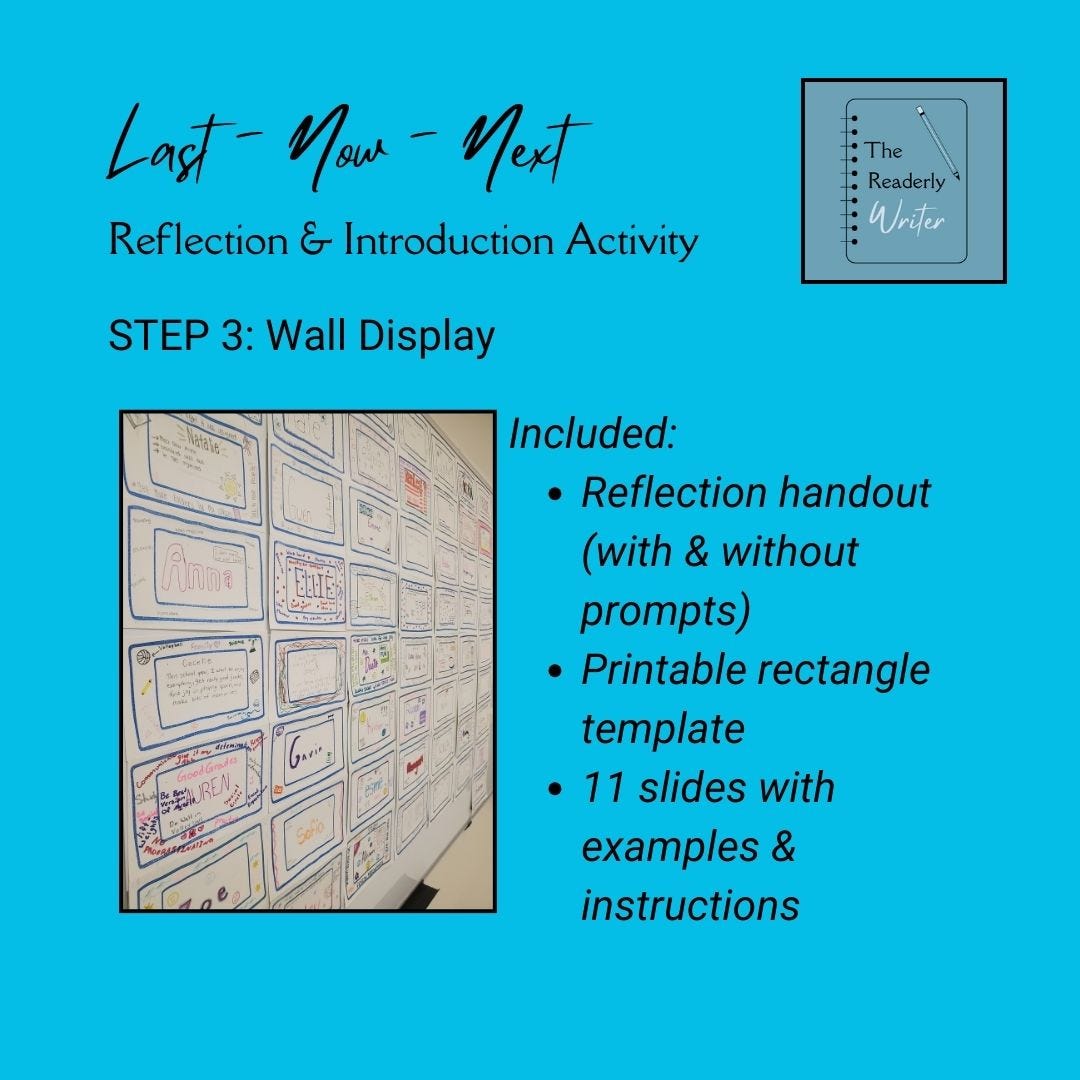

Last-Now-Next Community Wall: If you like the Last-Now-Next format, try this activity that doubles as a community-builder and a wall display (pictured below)! It’s currently $2 on TPT. Prep consists of printing some rectangle templates. And maybe making sure your markers aren’t all dead. That’s it!

For another wise novel that deals with Alzheimer’s, see Amy Tan’s The Bonesetter’s Daughter.

Indeed, as Julian and Martine fight to keep Nora out of the adult prison, Koval includes historical context about the myth of “super-predators” that led many states to charge juveniles as adults. Her expertise informs her characters without overburdening the novel with technicalities.